Rothschild Boulevard in Tel Aviv, July 2024. Foto: RLS Israel

Militarization, Conscription and Superpower Policies in Israel

A Brief Overview

People who come to Israel from abroad or Israelis who have spent long stretches of time in other westernized countries usually experience the shock or surprise of seeing so many guns on Israel's streets. Semiautomatic military rifles carried – often nonchalantly – by soldiers and settlers and guards and police as well as handguns on the hips of security guards as well as civilians.

The fact is, though, that most Jewish Israelis almost literally don't see these arms, don't notice them. It took my 3-year-old daughter freezing in fear on her first train ride (decades ago) to alert me to the rifle leaning on the knee of the soldier right in front of me. I hadn't noticed. We don't see them because at a very young age we acquire the habit of assuming they're only there to protect us and believing they're harmless – to us. This process of acculturation is one of thousands through which the consciousness of non-orthodox Jews in Israel is militarized.

Ongoing militarization

The term militarization refers to a process. You'll recognize the suffix from "legalization," for instance, or "modernization." Each of these denotes a social, cultural, political and economic process. Such a process requires the active participation and consent of the constituency or community that performs it and keeps it going, or at least of significant segments of that community. In the case of Israel's militarization, I'm using the term to point out an ongoing process, which originated in the colonial movement preceding the state and has continued, uninterrupted, ever since. I'll be sketching an outline of militarization in Israel and ending with a look at a significant crack that is opening up in it. As Jacklyn Cock described it in 1993: A distinction should be made between the military as a social institution […]; militarism as an ideology (the key component of which is an acceptance of organized violence as a legitimate solution to conflict); and militarization as a social process that involves a mobilization of resources for war. She continued: Militarization involves both the spread of militarism as an ideology, and an expansion of the power and influence of the military as a social institution. Here are some glimpses of how "militarism as an ideology" is actually spread.

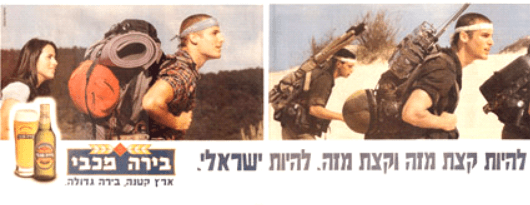

This is an ad for made-in-Israel Maccabee Beer. First, think about the message conveyed in the part of the caption at the bottom that says: "Small country." Since its foundation, Israel has branded and rebranded the state as small, embattled and threatened on all sides by multiple Arab states and huge numbers of (intentionally undifferentiated) "Arabs." This is the kernel of the sense of "existential threat" that drives Israeli militarization, regardless of how powerfully armed and politically supported the state is. Indeed, the horrendous Hamas attack of October 7th 2024 and Israel's genocidal retaliation; bombing, invading and starving the Gaza Strip, have demonstrated the enormous imbalance of power between these fighting forces, while a majority of Israelis have, nonetheless, apparently experienced the attack as evidence of a direct, immediate threat to their existence. Above that, where the caption says, "a little of this," "this" means being a combat soldier. And where it says, "a little of that," "that" means being an adventurous backpacker on the "big trip" that many young Israelis take after military service. Ideally with an admiring girlfriend in tow. Particular gender roles and in fact sexism are necessary ingredients of militarization.

This is another sexist, militarized, militarizing ad. No less than marketing baking yeast, it markets a particular concept of young men's role in society and of the supporting actress roles expected of soldiers' mothers.

There are literally thousands of ads and other cultural artifacts and rituals that work along similar lines. All of these carry out what Kenneth Grundy described as the: "… creation of a social atmosphere that makes military service seem attractive, military responses to policy issues sensible, and greater military strength and expenditure seem acceptable – one which in general prepares the population for conditions of siege and war." The investment in maintaining active consent to militarization is conducted through multiple channels that mutually reinforce each other. Visual culture – both commercial and non-commercial, literature, music, public architecture, very intensively the educational system, the media – all take part, often unintentionally. Individual interventions reflect the predominance of militarization – they are symptoms or results of it – and they simultaneously feed back into and reinforce it. It's a cyclic process.

Distribution of Common resources

Moving to a closer look at some nuts and bolts, or at how things work in conditions of militarization, Israel's overarching militarization can be identified in the distribution of common goods or resources. In this case, as in the case of cultural artifacts and education, the distribution results from militarization but also feeds back into the process – in a cyclic or spiral movement – and greatly entrenches and reinforces it. Here's a very brief look at three common resources.

The first one is land. In 2008, researchers Amiram Oren and Zalman Schiffer found that "almost 50% of the land in Israel is under some control of the army, some fully used as military facilities, and some of limited access due firearms training. According to Israel State Comptroller (2010) the army holds 39% of the land in Israel and enforces limitations on additional 40%, which is an even higher estimate.". In short, about eighty percent of Israel is either inhabited or constrained by security institutions such as the army, its bases, storage depots and firing ranges, or military industries and other types of security organizations.

A second common resource, political voice or power, also reveals extreme militarization: Ex-military officers have filled ministerial positions in all of Israel's governments besides the very first (that established the army). By 2022, fourteen Chiefs of Staff had gone on to national politics after discharge. Ten Defense Ministers were previously high-ranking officers, some of them Chiefs of Staff. The current government comprises three members (after Benny Gantz quit the emergency government on June 8th 2024) who were previously top-ranking military officers, another who headed Israel's General Security Service (Shabak), while the Minister of Education is a former fighter pilot. This overrepresentation has a largely invisible underside: Groups that are excluded from the top levels of the military or excluded from the army altogether are underrepresented in political office and national decision making. Women, Palestinian citizens of Israel, people with disabilities and others are all underrepresented. Political voice is slanted – towards the top brass.

The third common resource is Israel's government-approved national budget. In 2022, the approved defense budget was 12.7% of the national budget. This year, 2024, the approved defense budget (which is already undergoing significant changes due to the continuing warfare) comprised 20.1% of the national budget. The budget approved for creating employment, by comparison, was 0.7%, and the welfare budget was 2.9%. Both of these, despite the hard hits of covid from which significant parts of the population were still reeling. Almost half of the defense budget is regularly allocated to salaries. Not to soldiers' salaries. Conscripts are paid poorly and most families support them during service, effectively paying an extra, unofficial tax. In 2018 career soldiers, who stayed in the army after their tour of mandatory duty, earned an average wage that was over twice the average wage in Israel's work force. Probably even more problematic is the fact that career soldiers retire at age 45 in Israel and receive very generous pensions till the end of their lives, whether or not they go on to second careers. Unsurprisingly, given their political power, the top brass of the military and of other security organizations uses and controls a very large portion of the national budget. Most Israelis tend to miss or ignore this, however, in another example of the hold of militarization on the consciousness of individuals and the public.

In addition, very crucially, as sociologist Shlomo Swirsky has pointed out, the national budget reflects a policy of sustained conflict. It "reflects … a 'superpower' policy, not circumstances in which 'there's no other choice' … [but rather] a political strategic choice." This last point is clearly demonstrated in the current, unchecked government expenditure on continuing the warfare in Gaza and on spreading the eruption of violence northward, to Lebanon and Syria.

The myth of universal conscription

One of the main cog-wheels of militarization which isn't up for discussion, is universal conscription or "the draft." In a deeply divided, conflicted society, military service is presented and perceived, to a large extent, as the key to belonging. Remember the Maccabee beer ad that said, "To be Israeli." The recipe it implied was: Go to the army, go on the big trip, drink Maccabee. And, no less, be a man. Belonging in Israel is deeply gendered.

For a large segment of Israel's public, the ongoing cultural investment in continued militarization maintains an illusion that the majority complies with the draft and that everybody does their bit, because "there's no other choice" – we simply have to. In truth though, we don't. There are other choices. And there is much more evidence that this structure is a choice, that other choices are possible. For instance, In 2010, Asher Tishler, then the Dean of the Tel Aviv University Business Faculty, explained why the law of universal conscription remains in place and why the army goes to considerable lengths to demonstrate that it is enforcing this law. He said, "Every year the army drafts 15 thousand young men and women who it doesn't need, because their education and skills are insufficient. This costs 1 billion Shekels a year. [… The army] is compelled to draft them under the Military Service Law. … the manpower costs of a professional army would be 15 to 20 percent higher." That is, higher, compared to an army of conscripts. Clearly, according to Tishler, there is a choice. But universal conscription is viewed as more cost-efficient

The fact is, though, that in Israel today universal conscription is no longer the reality. Data released by the army shows a consistent, even if gradual, drop in compliance with conscription law – over decades. In 2017, just over half of non-Palestinian 18 years olds – 57.5% percent – complied with the draft and served full terms. A 2020 response from the Military Spokesperson to a freedom of information request submitted by the New Profile movement, revealed that in the cohort of 2018, just under 67% of those legally eligible for conscription were summoned to serve. Of these 57.6% of the men and 42.4% of the women actually enlisted. This is not universal conscription. If you think of it in terms of citizens, without automatically assuming that Palestinian citizens don't count, the number is well under half – about 40% of 18-year-old citizens.

At closer range, about 29.4% of the men called up were exempted from the army without serving at all. For years, orthodox yeshiva students, who are exempted almost automatically, have constituted another group that doesn't count in the thinking of many Jewish Israelis. Recently, though, in response to significant budget allocations for the orthodox community by the current far-right-orthodox government, large parts of the (mostly secular) resistance to the government push for anti-democratic legislation have also raised strong demands that orthodox men enlist. Regardless, in 2018, almost half (13.7%) of the men exempted from service up front (29.4% of those called up) were not orthodox yeshiva students. In recent years, according to Yagil Levy, who has studied the military for years, call ups to reserve duty have become more and more selective and complete exemptions from the military have increased significantly, making both conscripts and reserve soldiers a small percentage of the population. Even – or perhaps precisely – in the context of the warfare that is still ongoing as this piece is being written, former Knesset Member Ofer Shelach warned in May, focusing on reserve soldiers, "We're on the way to grey [undeclared] resistance. … The war is being conducted as if there were no shortages. Whether budgetary or in ammunition or manpower. But … there are shortages. Reserve soldiers are a limited resource."

So under the surface of the widely held view that "everyone does" mandatory military service and that it's "just what you do," if you're normal and normative, there is a growing social movement of de facto draft resistance. It is a complex movement with many different component groups, motivated by differing views and needs. I view it as a social movement of the kind that sociologist Alberto Melucci described in the eighties as underground, indirect and unformulated, sometimes even unconscious of itself as a resistance movement. On his reading, such movements are performed in the realm of daily cultural practices, within which alternative frames of meaning are created.

Israel's army is actually well aware of this movement or this social phenomenon, which is one of the reasons that it invests extra efforts in maintaining the illusion of universal conscription and the perception that there's no other choice. The public in general is far less aware of it, partly because the army takes care to obscure the data.

Israel's totally militarized response to the Hamas attack of October 7 2023 has seemed, on the face of it, to enjoy the support of a vast majority of the Jewish public, including large segments of the 300 thousand reserve troops who have reportedly answered call-ups and served extended terms. Moreover, the latter have apparently included significant numbers of men and women who were previously active and vocal in the unprecedented resistance to measures introduced by the far-right government, which brought millions out into Israel's streets over many months before October. But the underside of this massive support and active enlistment is virtually invisible and not well known. No transparent, aggregated data on the issue is available. It may take years until such data comes to light.

And yet, New Profile: The Movement to Demilitarize Israeli Society, has recorded a distinct rise in the scope of incoming calls to its counselling network, seeking information on the right to a discharge from the army and the mechanisms involved. From among the many thousands who don't enlist or secure early discharges, about 1,400 seek New Profile counselling every year. Now, the numbers are apparently growing. Tellingly, the calls are coming from individuals from varied backgrounds, in very different circumstances, some of which are not distinctly ideological. Accordingly, such circumstances can include exhaustion, depression, trauma, but also severe loss, or initial lack, of faith in the military as a system or in the goals of the current warfare, critical views of the failures displayed by the government dispatching the army, particularly of indiscriminate cruelty, killing and destruction and/or of the mishandled hostage situation. A minority of more overtly politicized refusers declare their objection, often through the Mesarvot network, and face likely imprisonment.

Militarization takes many routes. It is perpetuated and grown through multiple, varied means. In the US, for instance, the draft no longer exists but the country is still highly militarized, as evident in its repeated military invasions worldwide, largely commanding public consensus, in the predominance of the arms industry or the resistance of its legislature to curbing gun bearing and gun crime. Given the depth of militarization of Jewish Israelis' practices and consciousness, it would be a serious oversimplification to claim that refusal alone, as a movement or, if you like, as a social phenomenon, testifies to a progressive process of demilitarization.

Indeed, the civil resistance movement prior to October 2023 seemed to embrace militarized consciousness completely, organizing around ex-military officers and security officials as prominent leaders and largely (though not completely) overlooking the military occupation of Palestinian territories as the very heart and engine of Israel's anti-democratic trajectory. The months since, seem to have exhibited a powerful backlash to the limited critical space for reassessing these issues, that looked to be opening up within the pro-democracy resistance. We are accordingly witnessing trends and developments that are quite divergent and arguably opposite.

And yet, I believe it important to trace the fault lines along which they diverge or clash and to note that, at the very least, the young people who are the draft resistance movement are refusing to walk the walk of the unquestioned, militarized belief that "there's no other choice" and that each and every one of them must do their bit in the army. I don't presume to predict how far it will go or which directions it will develop, but I consider it meaningful that this process is ongoing and that it has been consistent for decades now.

Bibliography

Jacklyn Cock, Women & War in South Africa, The Pilgrim Press, 1993.

Shlomo Swirski, The Budget of Israel, ADVA Center, MAPA Publishers 2004.

Yagil Levy, "The War in Gaza Exposes a Disintegrated Israeli Army", Haaretz, March 19 2024.

Meirav Arlosoroff, "The IDF's money is flowing like water – and this might topple Netanyahu's government" TheMarker, May 17 2024 (Hebrew).

Autor:in

Rela Mazali ist eine israelische Friedensaktivistin und Autorin. Seit 1980 ist sie als Antimilitaristin gegen die Militarisierung Israels und die militärische Besetzung Palästinas aktiv. 1998 war sie eine der Mitbegründerinnen der feministischen Bewegung New Profile, die sich gegen die Militarisierung Israels einsetzt und Kriegsdienstverweigerer unterstützt. Im Jahr 2010 gründete sie Gun Free Kitchen Tables (GFKT), ein Abrüstungs- und Waffenkontrollprojekt. Sie arbeitete auch für Physicians for Human Rights-Israel und hatte eine beratende Funktion für das Internationale Rote Kreuz und die Ford Foundation inne.